|

|

|

STEELE CREEK NEWS

Steele Creek

Contributed to the World War II Effort (Part 2 of 3)

(May 1, 2016) In 1942 the federal government bought 2,260

acres of farmland in Steele Creek to build a naval ordinance plant,

locally known as the Shell Plant. After the plant closed following

the war, the land was developed as the Arrowood Business Park. It

has spurred additional industrial development along Westinghouse

Boulevard, both to the east and west of the original Shell Plant

property, and helped define the character of Steele Creek.

The main Shell Plant cafeteria

was located on what is now Westinghouse Boulevard about 1000 feet

east of South Tryon Street. The original building burned in 1944 but was

soon rebuilt. The

rebuilt cafeteria has been the location of various restaurants over

the years and is now home to La Poblanita Mexican Restaurant

and the Trap. It most likely is the only building still left today that existed

when the plant closed in 1957.

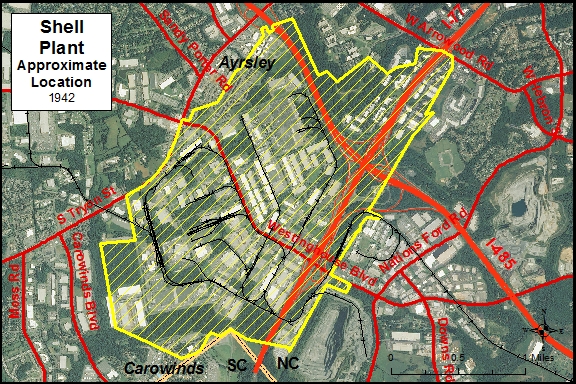

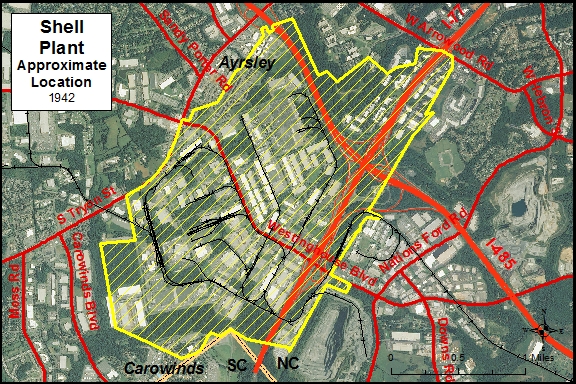

The map below shows the approximate area of the Shell Plant in yellow cross

hatch based on a variety of historic maps.

This is the second of three articles adapted from stories

collected or written by Walter Neely and published in Gleanings, Newsletter

of the Steele Creek Historical and Genealogical Society. Part 1

of this series,

Why Do We Have So Much Industry? It All Started with the Shell Plant,

covered the period that included the initial land purchases. Part 2 continues the history.

Homes, Land

Gone, Steele Creek is Reconciled to Big War Plant

On November

2, 1942, the Charlotte Observer published an article on the new war

plant. It described how an unsuspecting and peaceful community

discovered that it had been caught up in the swiftly-formed plans of

government and initially gave the cold shoulder to the

proposition

Construction turned Steele Creek

into a boom-town development. No longer a quiet rural community, it

seethed with activity and experienced an inrush of workers, many of

them living in an improvised fashion that contributed to the

impression of impermanency. The land that in peacetime yielded to

the plow changed to support the production of supplies intended for

death and destruction. Families had tilled this soil since before

the American Revolution and created a place centered in home,

church, and community development.

Rumors spread that the

government was considering the area as the location of a war plant.

Resentment followed the announcement that one of the best farming

areas of the state definitely would be bought by the government and

become a war plant.

They later learned that the other site considered along Paw Creek

had unsuitable terrain and land asking prices that were too high.

Who worked at the Shell Plant and how did it operate? In an article

written in 2001, Louis Pettus stated that at its height the plant

had more than 12,000 employees, over 90% of them women. Men were the

mechanics, guards, janitors and warehouse people, but only women

worked on the conveyor line, where they filled the shell cases – 16

shells to a can. Fifteen women weighed the powder and put it in the

shell cases. Some of the women rolled 4-inch strips of lead foil

which acted like grease on the inside of the shell casings. Two of

the lead foil rollers, and many of the other women, were

grandmothers.

One of the workers, Mae Pettus Griffin, later

said that she had never before done “public work,” but she had three

sons and two sons-in-law in service and felt it was her duty to back

them up. Almost all the women had only done house work or field work

previously. Seven days a week for the three shifts, buses collected the workers

from Gastonia, Concord, Albemarle, Monroe,

and other places in North Carolina and from Lancaster, Kershaw, Rock

Hill, Richburg, York, and other places in South Carolina.

Woodrow “Toby” Wilson of Indian Land in Lancaster County was one of

the building foremen. He remembered that smokers could smoke only in

the cafeterias. No matches could be brought in but cigarette

lighters were placed at intervals for the convenience of the

smokers. The cafeterias were about 200 feet from the main plant.

Everyone wore insulated safety shoes. The men wore uniform coveralls

with no pockets. The women wore uniform dresses. The floors were

concrete and kept shiny. Every 10 feet there were big doors built

for easy exit in case of explosion. None of the machinery was

electrical (although there were electric lights). All machines were

run by air. There weren’t any major explosions and only one

accident. One of the women workers lost her left arm. Powder was so

sensitive that if any were left under the fingernails, lighting a

cigarette would blow away the fingers. The plant won a number of

safety awards.

At first, workers on an 8-hour shift were

turning out 8,000 rounds of ammunition. At their peak, they were

producing 29,000 rounds a shift. Still, there were was only enough

labor to run two “load lines.” There was the capacity for a

third line, but labor was scarce.

Then something happened

that would have been un-thought of in normal times: black women were

hired to staff a shift on the third line. Toby Wilson was put in

charge–the only southerner to be a foreman. The other foremen were

northerners sent south from other U.S. Rubber plants. Mr. Wilson

said that he had one of the best, hardest-working crews in the

plant.

After May 8, 1945, when the war in Europe ended, all

other shell plants in the U. S. closed, but the Steele Creek plant

stayed in full production until Japan surrendered on August 15,

1945. Even then the plant did not completely close. A work force of

150-170 people stayed on until June 30, 1957, reconditioning the

unused shells returned by naval ships.

John and Irene Youngblood lived on what is now John Price Road but

then was York Road and boarded about

10 people at their house. At lunch time they fed 20 to 25 people

lunch every day in shifts. A bus went all over Steele Creek picking

up people to take them to work at the Shell Plant. The plant worked

24 hours a day, and some of the Youngblood boarders slept during the

day and worked at night while another shift worked during the day

and slept there at night.

Charlotte’s “Shell Plant” Vital in War and Peace

Another

article from the Charlotte Observer written just after the end of

the war said that investments in the plant had totaled more than

$300 million by May, 1945. During the war the Shell Plant

approximated the size and activities of a small city. Administrative

personnel from 40 states and over 10,000 employees worked in 13

production areas. Six cafeterias located in production lines and one

main cafeteria served thousands of meals daily around the clock.

There was a large medical department headed first by Dr. David

Welton and later by Dr. Grace Jones, both of Charlotte. First aid

stations were scattered over the plant. Medical staff numbered 52.

The safety department and a security force under the

supervision of Stanhope Lineberry and later Captain W. H. Nichols

under the U. S. Coast Guard maintained safety and security. The fire

department had 50 members, but only a few flash fires occurred in

loading lines during production. However, one chemical drying

building burned, and the main cafeteria was destroyed by fire on a

Sunday afternoon in 1944. The latter was rebuilt at a cost of

$75,000. The health and safety record of the plant was among the

best in the country. Due to perpetual vigilance, work in this

munitions plant proved safer than in the average industrial factory.

The peak production of 213,143 final rounds in 24 hours was

achieved on Pearl Harbor day in 1944. Production had far exceeded

expectations, and the plant had to establish its own ammunition

testing range in South Carolina.

On July 1, 1945, the Navy ordered

the first cutback in production and personnel because of a large

backlog of ammunition that had been built up for the fleet. Over 60

million rounds had been delivered in addition to millions of

specialized shells such as armor piercing, target practice, loaded

fuses, tracers and primers, and primed cartridge cases.

Two

days after the end of the war with Japan, the government production

contract with the U. S. Rubber Company was canceled. The Navy had

maintained inspection offices at the plant that employed over 100

Charlotte women, but the Navy took title to the whole plant site in

June, 1945. On November 5, the last departments of U. S. Rubber were

removed and the Navy assumed complete control. The shell plant was

commissioned a naval ammunition reserve depot as of this date. Many

millions of inert components in process of manufacture by other

activities were received and stored in over 70 magazines and

warehouses. The Charlotte Observer believed the reserves of

ammunition would prove valuable in the event of a future emergency.

The depot was also responsible for the preservation and

maintenance of line production machinery and tooling. Much surplus

equipment has been sold, but the remaining equipment was valued at

over $2 million.

The Shell Plant was originally constructed

to serve a limited war period. After the decision to turn it into a

reserve depot, several major maintenance projects were found to be

necessary, including the regravelling of miles of roads, reroofing

of nearly all buildings, the renewal of power poles and railroad

tracks and ties, and the repair and painting of the elevated water

tanks. Buildings and improvements were valued in excess of $6.25

million. Some buildings familiar to wartime employees were renovated

to new purposes.

The plant had a civilian personnel ceiling of

62, including maintenance men, ordinance men, and a small office

staff. After it was commissioned as a naval ammunition depot, the

commanding officers were Lt. Cdr. W. H. Ridpath, Captain F. P.

Wencker, Captain Alston Ramsay, and since October, 1948, Captain O.

P. Thomas, Jr.

This series will conclude in a few months with the final

installment. Walter would like

to interview anyone who has information about those who sold land

for the plant or worked at

the plant, or are familiar with the transition to a privately-owned

industrial park. Please contact Walter Neely by email

at wlewneemoo@aol.com if you can contribute to

the story.

Please email

info@steelecreekresidents.org if you would like to receive copies of the original articles in

Gleanings.

To comment on this

story, please visit the

Steele Creek Forum.

Click here:

to share this story to your Facebook page,

or click below to visit the Steele Creek Residents Association

Facebook page.

to share this story to your Facebook page,

or click below to visit the Steele Creek Residents Association

Facebook page.

. .

|